In my previous post on Bourgeois, I mentioned that "The return of the repressed" is one of only two segments of text printed on to pages of Bourgeois' fabric book, Ode à l’Oubli.

The talk was by art historian Claire Pajaczkowska, whose essay Tension, Time and Tenderness: Indexical Traces of Touch in Textiles I am currently reading for research.

Pajaczkowska began her talk by saying that Bourgeois came to textiles at the beginning and end of her life; she grew up in a family tapestry-restoring business, and created works from a lifetime's archive (or hoard) of clothes and domestic textiles in her final years. Bourgeois was interested in different types of threads; fibre threads, threads of drawing, threads of writing. Threads were woven into the search for her own identity. She was fascinated by the alchemy of tapestry and the repairing process; she once said that she "always had a fascination with the needle, the

magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair the damage."

The name "Louis" (or Louise) was a narrative thread running through the Bourgeois family; her grandfather and father were both named Louis, and her son Jean-Louis. Pajaczkowska remarked that the "e" which turns "Louis" into "Louise" is like a thread going back on itself, going back on a memory.

Pajaczkowska spoke of how the textile is an agent of boundaries which delineates; for example the boundary between clothes and naked skin, between the public and the private. She sees thread as a metaphor for filial relations, as in the threads of a family tree. She spoke of webs and networks as being the privilege of textiles.

Kristeva's theory of the abject, which I have recently been struggling with, came up in the conversation. Bourgeois would go to the meat market and buy huge haunches of meat which she would cast in plaster and then in latex. Rotting flesh is considered abject - it was once alive and now isn't, reminding us of our own mortality. Pajackowska argued that an untitled piece in the exhibition, a hanging slab of meat with genitalia and breast-like protusions, was more challenging than Bourgeois' latex pieces, due to the familiarity and domesticity of the pink towelling it is made from. In fact, the domestic materials Bourgeois used, constructed using child-like techniques, could be considered the opposite of the "serious" art world. Bourgeois operated beyond "taste", and there is a horror (or abjection) of this for the art world. The domestic materials, combined with the crude finish/stitching may horrify "fine" artists. Pajackowska spoke about the "seemingness" of the seams of Bourgeois' work.

The other major theme of Pajaczkowska's talk was that of "holding", both with the hands, and that of immaterial, conceptual containers. All textiles have a tactile quality, but many of the pieces in the exhibition had a particularly touchable quality; I wanted to hold them but couldn't due to the ettiquette of the gallery visit.

|

| Untitled, 2001, fabric and aluminium. Similar to the fabric heads in the exhibition at The Freud Museum. |

Stitches hold everything together (back to the reparative power of the needle again).

The child psychoanalyst DW Winnicott came up with a concept of holding, which he saw as an important component of a mother caring for her child. This "holding" is explored in Bourgeois' piece The Dangerous Obsession, which depicts a cloth woman holding an orb which could represent a new-born child. The pair are enclosed within a glass dome, perhaps demonstrating their all-absorbing relationship. The title of the piece could refer both to motherhood which overtakes a woman's life, and to the creative process.

|

| The Dangerous Obsession, 2003 |

Interestingly, Winnicott wrote that the child moves on from being held by its mother to holding a "transitional object" made of textiles, such as a comfort blanket or soft toy.

Pajaczkowska explained that the making of objects "held" Bourgeois; she was wrapped up in it, as soon as she had finished making one she would move on to another.

Visitors to the exhibition are then "held" in investigating the work.

There is holding in my book; the book will hold the pages together, and the pockets handkerchiefs and the history and stories which go with them, as well as soft sculpture pieces.

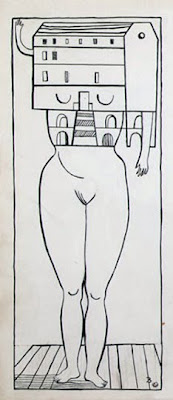

I was pleased to learn at the talk that there is a playful aspect to Bourgeois' work. She enjoyed punning and language play, for example in her series of Femmes-Maisons; "femme-maison" means "housewife" in French. In this series, Bourgeois translated this into literal "house-woman" - women with houses for head.

|

| Femme-Maison, 1945 - 1947 |

This appeals to me as a writer whose work often employs punning.

i had never thought of winnicott's concept of transitional objects in relation to the textiles i'm stitching, but it's a great connexion... and surely part of the reason why stitching is so helpful in art therapy and memory work. thanks for unpacking this essay and exhibit for us!!

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome!

ReplyDelete